our message

to the outside world

is clear even if our reasoning is “for the children”

we are still free

to endorse the soil

Linda Vilhjálmsdóttir, ‘Frelsi’ (Freedom)

Performance as a promise of beauty

Adrian Krężlik

Oceans filled with plastic straws, severe droughts in the Middle East, dynamic and dramatic climate change, melting glaciers, massive extinction of wild animals. The Anthropocene is a euphemism for violent human behaviour against our planet. Our consciousness is rising, we sort waste and sometimes even upcycle rubbish, some switch to collective transport, others decide to cut-down unnecessary expenses to stop the raging consumption… All individual actions undertaken by us delay the (in)evitable catastrophe. However, it’s just a drop in the ocean.

Us, the architects, should take action as a group. Our commitment should be to introduce mechanisms to minimize the negative impact of construction. The way we design drastically impacts our planet. The above is confirmed in a simple (although incomplete) statistic: in the United States, buildings (as well as their inhabitants) and the resources used to build and maintain them account for 38% of carbon dioxide emission and 72% of electricity consumption.

Greenwashing

The Brundtland Report from 1987 introduced the notion of sustainable development into public awareness. The document lists environmental protection as one of the key issues of the global political agenda. It announces to “re-examine the critical issues of environment and development and to formulate innovative, concrete, and pragmatic action proposals to deal with them”.

Unfortunately, we have ignored the drawn conclusions and the calls for action. Instead of establishing structural procedures, we surrounded ourselves with a meaningless greenwashing bubble. The term sustainable development has become a keyword in countless presentations and speeches that don’t bring positive change. In this situation, us, the architects, should be able to separate real acts from apparent ones. Architects are in a large part responsible for the rushing climate change. As long as humankind spends most of the time in the built or natural environment, designers have to advocate for ecology.

One of the examples could be the smog – a currently extremely hot topic, particularly in Poland, which has the worst air quality in Europe. At a glance it seems that design and smog are not connected. However, poor architectural design and erroneous urban planning are one of the main causes of smog. The creation of smog in urban areas depends on a number of factors. The main sources of smog include: vehicle traffic, inefficient coal-fuelled heating systems and industrial emissions.

The first factor, namely vehicular emission is responsible for the creation of over 50% of smog in the greater part of urban areas. A moving car or motorcycle pollutes air in two ways: with fumes and airborne particles. Smog comprises of airborne by-products of combustion, carbon monoxide (CO), nitrogen oxides (NO) and other pollutants reacting with the sun or heat. The invention of high-performing motors and electric cars leads to mineralization or even elimination of the above aspect. We should however be aware of the fact that electric vehicles will not solve the problem entirely, because the only difference between them and regular cars is fuel (an electric car also requires energy and its batteries are produced from semi-precious, rare metals). Moving vehicles produce and stir huge amounts of tiny pollution particles from brake and tyre dust.

Low population density, urban sprawl, progressive process of urbanizing green areas and wind corridors, modernistic zonification, inefficient public transport, lack of bike paths or dangerous ones – all of the above forces inhabitants to use cars that pollute the air. Improvement of air quality is possible if cities were designed in a decentralized way, pedestrian- and cyclist-friendly, with integrated green areas, and fast, efficient and clean public transport.

Numerous environmental rapports prove that inefficient heating systems are the second cause of smog. The aim of heating is to ensure or enhance user comfort. Engineers analyse heating comfort when designing heating, ventilation and air-conditioning. The amount of primary building demand for heat depends on the shape and position of the building, orientation, implemented passive solution, the quality of used materials, and the wall-to-window ratio. An architect has the greatest impact on the above-mentioned aspects.

In his book Heating, Cooling and Lighting, Norbert Lechner states that good architectural decisions could reduce building demand for energy by as much as 80%. Emanuele Naboni and her colleagues from KADK (The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts) in Copenhagen are searching for architectural solutions to reduce energy-consumption. Engineers from the world’s largest companies such as ARUP or Buro Happold are researching the possibility to modify architectural design to improve the performance of buildings. The “engineering” of buildings a posteriori cannot bring as good results as a simulation conducted a priori or a well-thought-out project.

Green Certificates

LEED, BREEAM, WELL, DGNB are examples of the most popular certification systems that entered the market in the last decades. It might be surprising to see a building created in the middle of the desert to be awarded an environment-friendly certificate. We might ask ourselves the following questions: how do they deliver materials to the building, how does it influence the ecosystem, how is this building reached by car, and how much energy expenditure does it require. Such examples may raise distrust – and it doesn’t come as a surprise – certificates are granted based on points awarded in a number of categories (depending on the function of the building: localization, accessibility, consumption of water and energy, use of materials and other aspects receive a certain number of points). In the case of LEED, a maximum of 110 points may be earned but a certificate is awarded for at least 40 points. The conclusions are obvious.

Not without reason the architectural industry believes that certificates are presently market tools. According to Gang Chen, author of many books concerning LEED, branding and marketing are one of the most significant benefits of the certification process (however, with the above in mind, I believe that if a building is in fact a positive example of a building nourishing the environment, it should be widely discussed). On the other hand, there is one more important benefit resulting from such approvals and certificates of quality.

In the introduction to LEED Core Concepts its authors present the concept of the “triple bottom line” coined by the British economist John Elkington. He believes that every venture should consider three aspects briefly defined as people, profit and planet. Adoption of the above approach forces the investor, designer and all other parties involved in the process of design, construction and maintenance to adopt a holistic approach.

The development of certificates was supposed to improve architectural standards and in turn the comfort of life, and to reduce negative impact on the environment. There has been an increasing tendency for architects to comply with the guidelines outlined in certificates, which are more rigorous than legal regulations. This way they make sure that their project responds to the present demands of the market. Certificates are founded on actual scientific research and reflect rapid social transformations. Let us look at the example of indoor daylight. The Polish law is based on the Soviet (!) model from the 1960s while LEED uses expertises from the last 15 years.

The dissemination of Polish architecture is the key to understand it, and to gain more knowledge about the quality of architecture. Magazines, critics, participation in international events and digital publications and guides have helped those of us, who live far from the Polish creative epicentre, to acknowledge that things are bubbling in this country. But it is very difficult to find – at least in English – a global critical discourse inherent in the work of Polish architects. It is very difficult to find architects who are able to combine a critical approach with implemented projects of outstanding architecture.

The presence of critics of architecture is essential to understand the particular Polish context and to be able to place it in a broader international context, but when we come across architecture of imagination, we know that it has the capacity to understand the global context, respond to it, continuously build a personal critical discourse through implemented and not implemented projects and, at a certain point, to become influential to a certain group of people.

Our commitment should be to introduce mechanisms to minimize the negative impact of construction. The way we design drastically impacts our planet.

Responsible design

Doctor Kristof Croll from the University in Hong Kong claims that if highly educated and honest architects designed good architecture, a detailed building code would be obsolete. The researcher points out that top-down regulations may impede the creativity of architects. He gives the example of Hong Kong where it is basically impossible to design a building not shaped as a box. However, architects are taught the correct corridor width, the amount of indoor light and other aspects of well-designed architecture already during studies. According to Croll, the building code is an act of distrust towards the architectural industry. Certificates could be seen in the same light – if architects designed comfortable and environmental-friendly buildings, certificates would be obsolete.

Adam Ozinsky, environmental engineer from the Berlin studio ARUP expresses similar views. He proposed a concept of honest architecture. Adam suggested that architects should look for passive solutions, forget about the obsolete way of thinking with forms, and consider embedded energy (energy that was used when working on the product). Adam reminds us about the responsibility of an architect towards clients, environment and society. He advocates for using simulation tools at the early stages of design, which allows us to see how the building would work.

Integrated design – a closer collaboration between engineers and architects should be a standard procedure, not an exception. Honest architecture as well as certificates are also founded on an open feedback loop and a circular design process instead of a linear one.

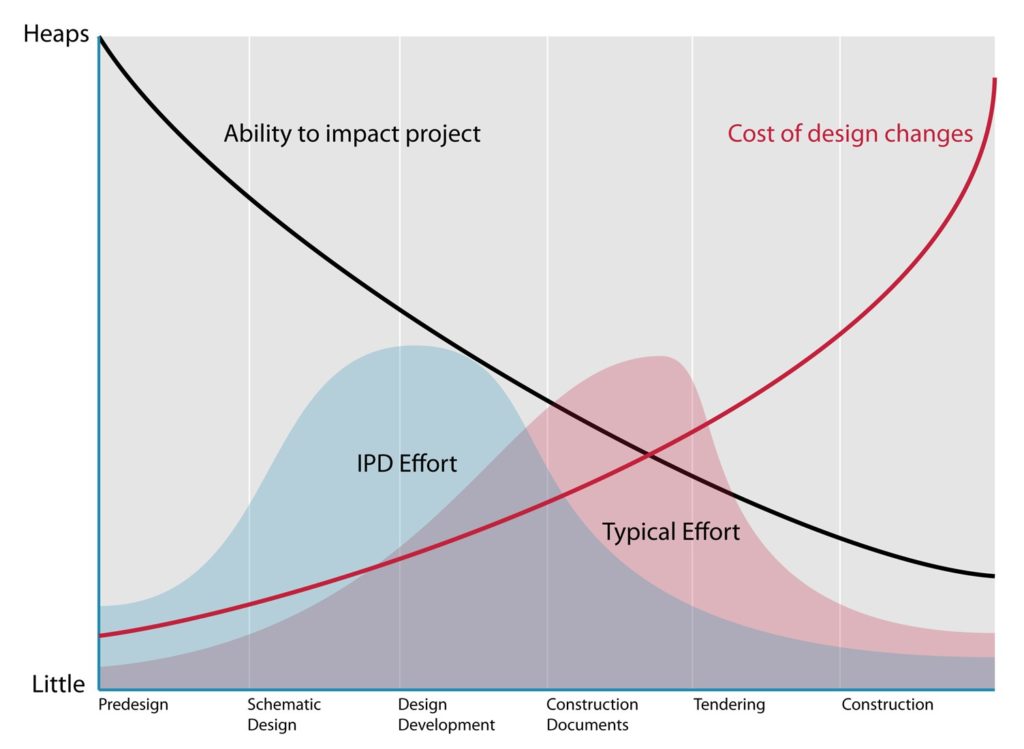

It is worth mentioning the Paulson’s curve, which shows the benefits of making decisions at early stages of designing when an architect (and an engineer) has a lot of options, and the disadvantages of making decisions at a late stage, which generates high costs and allows to exert small influence on the final result. In order to be able to make decisions at an early level, a design team has to work together on the project from the very beginning. Patrick McLeamy, the CEO of HOK (the largest U.S.-based architecture-engineering firm) used the Paulson’s curve to discuss architectural design, construction and maintenance. McLeamy postulates to introduce integrated design to the earliest stages of design. The above-mentioned curve is another element, which proves that performance should be considered a key factor in architectural design.

Green avant-garde

The great majority of architects treat passive design or ecological design as a separate “branch” of architecture. Oddly enough, eco-aware architects form a separate cast resembling a hippie subculture. They refuse to wear black shirts or to discuss new projects by John Pawson or Lina Bo Bardi’s brutalism. They are often associated with the so-called vernacular architecture (rooted in local tradition, created by locals); they do not appear in popular magazines or Internet portals. Only few come close to mainstream. Vo Trong Nghia, Stefano Boeri and Hiroshi Sambuichi are possibly the most (or maybe the only) recognizable representatives of the “green avant-garde”. Understanding the environment is the starting point for their projects.

Currently many of the largest architectural offices (F+P, IDOM, HOK, SOM) employ teams responsible for sustainable development. Unfortunately they are often not design teams but auxiliary teams that attempt to tweak existing projects, so they only exert a slight influence on the final result.

With the development of science and technology, ecological design received new tools and methods. One does not have to be a specialist or an eco-aware architect to use it. Passive design, biomimetics, vernacular mimicry and environmental computer simulation are the most important tools developed to create responsible and truly green architecture. The above-mentioned solutions bring about a new aesthetic and architectural language; they constitute an alternative for the pervasive pseudo-modernism and minimalism.

Let’s take up this challenge

Ecological design is not about choosing the best materials or excellent solar-powered MEP systems – at least not from a viewpoint of an architect. The above features introduced a posteriori should be considered as a supplement to the project, which is supposed to further increase the comfort of the designed space and to minimize its negative impact on the environment.

Contemporary architecture has its formal and spatial roots in anti-ecological modernism. In order to improve it, one has to use complex ventilation, heating and sanitation systems, which are obsolete in a well-designed form. An architect has a different repertoire of tools at his/her disposal: position on the plot, geographical orientation, shape and formal solutions, such as position of windows, roof shape, its type and proportions.

It is worth analysing solutions in rural architecture, the above-mentioned vernacular mimicry. Traditional, non-modernized rural areas provide examples of buildings perfectly in line with the local climate, air circulation, roof shape, and window position. Władysław Matlakowski broadly discusses this subject in his books Budownictwo Ludowe na Podhalu (Folk architecture in Podhale) and points out that all 19th-century mountain cottages have windows facing towards the south in order to let as much natural light as possible, or a broad eave protecting against the rain. Vernacular mimicry is a branch of knowledge studying and popularizing such approach. It is worth mentioning the book The Barefoot Architect by Johan van Lengen, which shows how formal solutions in various climate zones deal with the specificity of climate. For instance, the book discusses traditional solutions to ventilation in hot and humid climate. It explains how the roof shape and height, the size of the eave, the localization and size of windows mat influence air circulation.

Certainly, it is a challenge to observe the above-mentioned design methods and to adapt them to the requirements of large investments. But it is a challenge we have to take up. Traditional vernacular solutions used low-cost solutions (energetic and financial), which should serve as a model of architecture in a given region, not an antique-shop curiosity.

What is important?

The international style developed in the 1920s and 30s characterized by mass-produced iron and steel buildings with large glass facades, which rejected local building tradition and ignored climate zones, has irreversibly transformed the industry. Offices located in hot and humid zones aim to resemble offices in the Netherlands or Germany. Rejection of regionalism and unification in the name of aesthetical values might have been one of the greatest mistakes of modern and contemporary architecture.

We should ask ourselves how to take the advantage of traditional knowledge and modern technologies. For instance, the above-mentioned localization of windows in mountain cottages on the southern façade. Simulation tools allow us to find out how much daylight enters through a window located on a given façade, what happens if we change its size, use another time of glass, etc. Design that uses simulation ensures a better performance of the building.

Today’s software market offers a plethora of easily accessible simulation tools. The new generation, fluent in computation, quickly grasps new ideas and learns the new software. It might bring a new unparalleled value to companies. Even a simple simulation of the amount of daylight or energy improves the chances of designing a better performing building. This approach requires an architect to have better knowledge and skills, which is unacceptable for some of us. It is an unprecedented situation for architects but rapid urbanization forces us to take appropriate action.

Architectural simulation frequently points us towards unexpected spatial and aesthetic solutions. We might or might not use them. Once more we are faced with many questions: why the aesthetics of our everyday lives is better that aesthetics suggested by the simulation? Which elements do we find essential? Are the aesthetical standards of Palladian or Le Corbusier’s architecture more important than the environment and common good?

Unikato, multifamily house designed by Robert Konieczny KWK Promes, This is the first building in the world whose façade color was created as a result of conducted research on air pollution in Silesia, Poland.

Green avant-garde

The great majority of architects treat passive design or ecological design as a separate “branch” of architecture. Oddly enough, eco-aware architects form a separate cast resembling a hippie subculture. They refuse to wear black shirts or to discuss new projects by John Pawson or Lina Bo Bardi’s brutalism. They are often associated with the so-called vernacular architecture (rooted in local tradition, created by locals); they do not appear in popular magazines or Internet portals. Only few come close to mainstream. Vo Trong Nghia, Stefano Boeri and Hiroshi Sambuichi are possibly the most (or maybe the only) recognizable representatives of the “green avant-garde”. Understanding the environment is the starting point for their projects.

Currently many of the largest architectural offices (F+P, IDOM, HOK, SOM) employ teams responsible for sustainable development. Unfortunately they are often not design teams but auxiliary teams that attempt to tweak existing projects, so they only exert a slight influence on the final result.

With the development of science and technology, ecological design received new tools and methods. One does not have to be a specialist or an eco-aware architect to use it. Passive design, biomimetics, vernacular mimicry and environmental computer simulation are the most important tools developed to create responsible and truly green architecture. The above-mentioned solutions bring about a new aesthetic and architectural language; they constitute an alternative for the pervasive pseudo-modernism and minimalism.

What’s next?

The responsibility for our planet is an integral part of architect’s job. Architecture should be based on a good project. Today we cannot afford grandiosity or ignorance.

In my professional work people are often met with lack of understanding. I have experienced it in a meeting with David Chipperfield Architects, who served me, still a naive idealist, a very cold shower. In response to my suggestion that a slight rotation of louvers would let notably more natural daylight into the room, they issued a statement: “our solutions are founded on aesthetical aspects, we are not interested in changes you suggested”. There is a saying that the fish rots from the head. I believe that people we consider to be masters, such as David Chipperfield, should set an example and define new directions.

Fortunately – speaking from the perspective of common good and not architecture – investors make a lot of decisions (not architects). Investors, quite obviously, attempt to reduce costs. Cost cutting means saving and, according to MacLeamy, we can save most in building maintenance. Green buildings are energy efficient due to their specificity. For this reason, investors will be looking for ecological solutions. As I have already mentioned, they can be achieved with advanced systems, but good architectural projects embedded in the natural environment are a better option.

It is estimated that in the near future (in 2023) the global population is going to reach 8 (!) billion people, 60-80% of which will be living in urban areas. It is not clear how much of the built environment was designed by professionals, but even if it is a tiny percentage, architects are responsible for creating positive patters of behaviour. Architectural design in a spirit of sustainable development is our obligation. Alternative approaches prove ignorance of the issue of the violent escalation of the degradation of our planet.

Architectural aesthetics reveals social development: French baroque palaces reflect the deep pockets of their founders; modernist, prefabricated housing complexes from the 1960s and 70s remind us of rapid urbanization and the attempts to respond to the problem of shortage of flats. Today, we are dealing with rushing global warming and an exploited, impoverished planet. New aesthetical solutions stem from building performance, harmony with nature, and from where and how it draws water, light or thermal power. It appears that today formalistic approach to architecture is obsolete and reduction of architecture to classical or modernistic beauty is a crime.

Adrian Krężlik – an architect, educator and creative entrepreneur dedicated to application of contemporary science and technology into design processes. Founder of an educational platform Architektura Parametryczna and a start-up Parametric Support, which researches the use of Artificial Intelligence for automation and optimization of design processes. He teaches at Weißensee Kunsthochschule and the School of Form.