Architecture or money?

The logical disjunction in the title suggests that one can either be an architect, or run a firm. In most cases, architects are incapable of combining creativity and the ability to successfully manage a lucrative business.

Adrian Krężlik

Design hunger, a giant ego and a “responsibility” for saving the world with design make us blind. Understanding the market or making responsible business decisions that pertain to substantial parts of our activity, has been erroneously pushed into the background. A short-sighted approach often gets architectural companies into trouble, i.e. financial, and forces them make unethical and unwanted decisions.

In a capitalist economy, wealth is measured with money or assets. As long as we operate within this system, money is the key driver in architecture. Although architects tend to visualise themselves as grand creators, for whom money is not an issue, they are not. I would dare to quote the classic, Karl Marx: “A writer is a productive labourer not in so far as he produces ideas, but in so far as he enriches the publisher who publishes his works, or if he is a wage-labourer for the capitalist”. One could draw a parallel to architecture, with an architect being a productive labourer, enriching the general constructor or, in most cases, the real estate development company. Design activities constitute the building lifecycle value chain.

Economic sciences and market studies consider architecture to be part of the AEC (architecture, engineering and construction) sector. Reports suggest that AEC is responsible for about 10% of gross domestic product and the numbers keep growing. Every year, the labour division becomes more precise. New professions emerge and take over a portion of typical architectural jobs. The ongoing discussion on automation that looks to replace human beings in the most tedious activities could be a blessing or a curse for architects. According to the optimistic scenario, we might receive the opportunity to work only on the most challenging and most interesting aspects of design, and less on the production process. In the worst-case scenario, advanced software and IT companies would drain all the money from the industry.

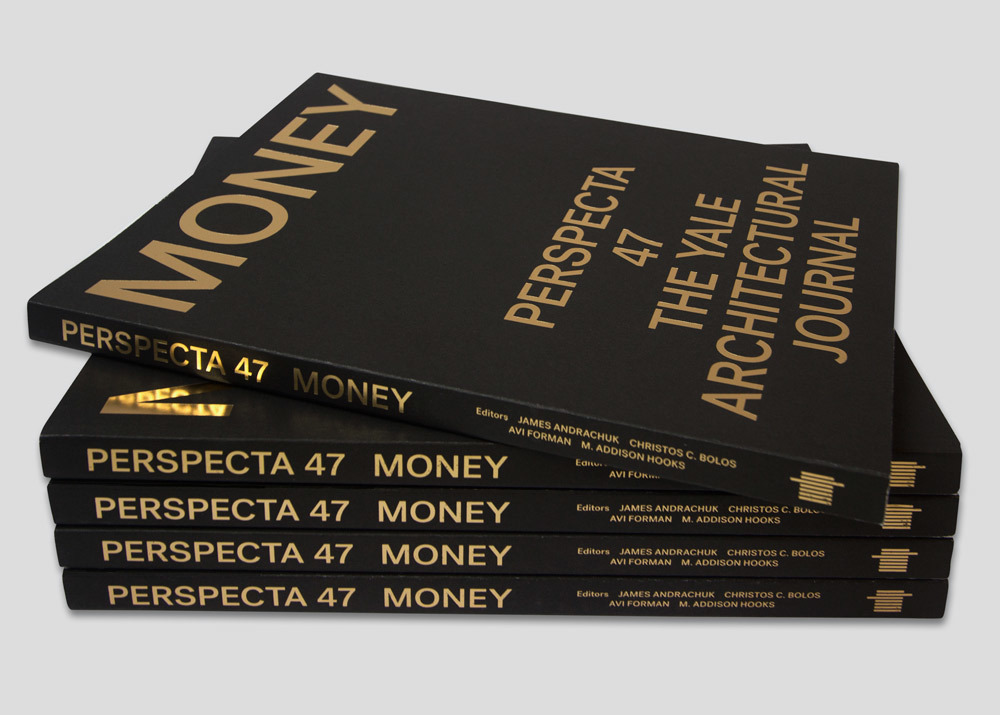

Perspecta, The Yale Architectural Journal

Inability to satisfy ambitions and the financial instability

Academia tends to deny the importance of an investor and educates generations of castle-builders, who enter the market without the essential skills. A university should provide a young professional with a legitimate business, administration and management basis. Architecture market comprises small and medium companies, and professional freelancers. It might be impossible or inaccessible to hire a specialist to create a business plan and define a business model for a new company.

Yale University pioneers in understanding and acknowledging the value of money. In 2014 it published „Perpecta 47: Money”. On over 100 pages scholars and heads of the most important studios (Gehry, Rappaport, Zaera-Polo, Eisenmann, Pelli, Carpo) discussed the importance of money and clients in design and the construction process. Later, the issue was taken up in a university course entitled „Exploring New Value Propositions for Practice” and led by Phil Bernstein, a former vice president at Autodesk. Students were given an assignment to create a business plan that creates an actual value and profit. Bernstein encourages students to perceive architecture as part of the supply chain. He raises the questions about value proposition, rather than hourly rate fees or lump sum payments.

The absence of business classes in a academic curriculum and the general belief that there are not needed seems to originate from the first schools of architecture. Professional education started to take shape in the late 17th century. The first to teach architectural competences was the Academy of Fine Arts. The school didn’t train architects but gave them adequate artistic education, as professor Omilanowska reminds us in her writings. Military schools, on the other hand, trained students in what we call today civil engineering.

The first group graduates envisioned themselves to be artists, creators, destined for greatness. Unfortunately, this attitude has spread over the years to all architecture graduates, including those from military schools (or École polytechnique in France and later Bauakademie in German-speaking countries). Unmodernized educational system brings about an emergence of ideas, such as the Free School of Architecture, which focus on architectural history and theory, design and aesthetic theory, practical and vocational topics, and philosophy, excluding design studios. Significant gaps in knowledge, reflected in the architectural work market, forces numerous professionals at a mid-career level to move to a different market segment, or leave the industry altogether. Inability to satisfy ambitions and the financial instability forces them to give up their dreams and reinvent themselves.

“Significant gaps in knowledge, reflected in the architectural work market, forces numerous professionals at a mid-career level to move to a different market segment, or leave the industry altogether. Inability to satisfy ambitions and the financial instability forces them to give up their dreams and reinvent themselves”.

Josh Rose/ UNSPLASH

Modern slavery is a fact

After the second or the third year of bachelor studies, most of the young not-yet-architects begins to fish for an internship. Then, they hit a wall for the first time. Some offices accept them for a three-months unpaid period. The list of required skills is frequently chaotic and extensive. A very young apprentice needs to be familiar with most of the software available on the market, must be eager to work hard, meet tight deadlines, and often to sacrifice the entire summer. The deal seems to be simple. An intern works in an office, most likely with his/her own laptop, often on competitions or early-stage design projects, builds physical models or produces renders.

Gaining knowledge and an enriched CV are the remuneration. It does not matter that the company gains recognition, delivers higher quality projects or simply earns money resting on the shoulders of interns – interns that architects do not afford to pay. I have heard countless examples of offices running on interns, four interns under the supervision of a more experienced colleague. Isn’t an internship a school for young architects? It is not just a school of architecture, but also a school of standards, ethics, values and work culture. We should see interns as ourselves in the past. Teaching them is a duty.

An action has been taken. For instance, in 2011 RIBA (Royal Institute of British Architects) introduced a “statutory minimum wage clause covering post-Part 1 students working for architects in the RIBA’s Chartered Practice scheme”. The President of RIBA warned that companies providing internships not following the rules would lose their licences. Nonetheless many British students continued to report widely spreading unpaid internships. Two years later, RIBA faced the problem again and called students to report companies that offer unpaid architecture internships, and said that it “deplores any architects treating students this way”. The Australian Institute of Architecture has expressed a very similar approach, stating that it is illegal to hire unpaid manpower. On the other hand, a shameful example came from one of the most awarded and esteemed architect, Sou Fujimoto. In an interview for “Dezeen”, he said: “If you have to pay all the interns, then we’d definitely have to limit the number of the interns and we couldn’t provide such an opportunity for students or younger people to gain experience in […] architecture”.

Architecture students who work full- or half-time in Polish architecture companies provide alarming information. Remuneration varies, apprenticeship is short, usually during the summer, and it is usually unpaid. In practice, in case of a long-term “employment”, the “wage” could be as low as 2 Euros per hour in some of the most prestigious companies (!). It is clearly against the law. The Employment Code strictly regulates the internship agreements. It appears that a modern slavery is a fact. I urge professional associations to take action.

There is an array of certain skills needed to run a business. I would like to emphasize that if a business does not have essential skills to generate enough profit or to self-sustain, it should not be on the market. This might sound coarse, but this is the truth. Architects were the ones who have shaped the market in the way that running a fair and sustainable business might be impossible. I do strongly agree with the opinion expressed by Mushtaq Saleri, the Associate in British Ellis Williams Architects in an interview for the “Architecture Journal”: “If we continue the downward spiral of suicidal fees somehow justifying exploitation, the profession will never recover to the levels where we can properly employ graduates in sufficient numbers”.

Adrian Krężlik – an architect, educator and creative entrepreneur dedicated to application of contemporary science and technology into design processes. Founder of an educational platform Architektura Parametryczna and a start-up Parametric Support, which researches the use of Artificial Intelligence for automation and optimization of design processes. He teaches at Weißensee Kunsthochschule and the School of Form.