Long live Modernism!

2018 in Polish architecture from a foreign perspective

Andrian Krężlik

I should probably begin by stating that I believe to be familiar with the state of Polish architecture – I follow social media, I’ve spent nearly one month in Poland and I’ve participated in the Conference on Architectural Competition in Chęciny, thus my viewpoint is both emigrational and national. Following Lefebvre, I am not reducing architecture to implementation, because it is an entire system consisting of texts, exhibitions, projects, discussions, etc.

In my previous article on Polish architecture from a foreign perspective, I wrote that Poles are hardly present outside Poland and too immobile. We don’t establish contacts; we don’t design groundbreaking projects or conduct innovative research in the field of architecture. Perhaps this is the reason why the majority of the publications concern the history of 20th-century architecture – a subject, which is nota bene also strongly present in Polish architectural culture in the form of lectures, publications or walks.

The Venice Biennale

The subsequent edition of the Venice Biennale is perhaps the most important event present in the international discourse. During the Biennale, 63 countries presented or were supposed to present the issues they are currently dealing with, their most significant projects or their future plans. Poland was represented in the national exhibitions by Anna Ptak and Grupa Centrala with the project the Amplifying Nature. The project was selected in the competition organized by Zachęta – National Gallery of Art. Without a doubt, the Anthropocene is one of the most crucial problems we have to focus on. The issue was presented using the examples of the architectural projects of the Hansens, Jerzy Sołtan, Jacek Damięcki and one project designed by Centrala, as well as the spatial installation by Iza Tarasewicz. Given the above-listed components, we could have expected a great exhibition, but it wasn’t. Biological processes were treated as phenomena or aesthetic elements, the floating models were impressive, and the opened roof opened stirred emotions. However, I see another aspect of water – depletion of resources and severe droughts in the Middle East, no small retention programs in cities, no systems for storage of rainwater in buildings, use of drinking water (!) for watering gardens. Discovering former or alternative names for rain could have been surprising for Matlakowski at the decline of the 19th century in Folk Architecture of Podhale (Budownictwo Ludowe na Podhalu), but is it the right subject for an exhibition in Venice? One can explore the Aquatic Architecture studio run by Andrés Jaque at Columbia GSAPP to discover the younger generation’s approach to the issue. Experiments were the domain of the modernists, and it is the domain of Columbia students. Unfortunately, for me, Centrala’s non-experiment is vague and purely formal. The exhibition seems quite indecipherable. Its objectives were partially explained later, in the press. With the overload of information at the Biennale (I suspect that most of the visitors are there for 1-2 days), it is important to send a clear message, perhaps even infantilize it, but to convey the ideas and invite to further reflection. Just take a look at the flawless proposals put forth by Australia and the Scandinavian countries, or the Swiss project playing with the scale. The Polish pavilion was discussed in several publications in the media, which is certainly a good sign for Grupa Centrala and the Polish modernism.

However, no Polish architect or curator was invited to the core exhibition at the Giardini.

(c) Amplifing Nature exhibition, photos: Anna Zagrodzka

Exhibitions, conferences, fairs

Since 2016 Berlin’s Architektur Galerie has expanded its offer to include Satellit in Friedrichshain: a district with techno clubs and alternative art. According to gallery owners, young (!) architects and researchers present their projects there. This year, Robert Konieczny had a collective exhibition with Christoph Hesse and Snorre Stinessen. About two months later BBGK Architects had an individual exhibition, which was the first individual exhibition of Polish architecture in the Berlin gallery.

(c) Vita Contemplativa – Hesse / Konieczny / Stinessen, Photos: Jan Bitter

(c) Manifesto of Prefabrication – BBGK Architekci, Photos: Bartek Barczyk

The Polish Institute in Berlin also attempted to introduce Polish architecture by organizing two exhibitions. The first was the Architecture of the VII Day – a study on the construction of Polish churches in the second half of the 20th century. It is a rather hermetic and historicizing subject. The Polish diaspora constituted the majority of guests attending the opening. It seems pertinent to note that in comparison to the momentum and quality of the architectural exhibitions of the Gropius Bau Museum or even the independent Spektrum Gallery, the Polish exhibition was pathetic – boards stuck on foam and cables glued to the floor reminded us of the Polnische Wirtschaft – a pejorative, xenophobic term used to describe projects implemented by Poles. The second exhibition at the Polish Institute entitled “Algorithms of Modernity” depicts the history of 1918-1939. The only question is: what for? The designers of the 1920s have ended their careers long ago and they don’t bring any added value to culture. And what if we discussed thriving contemporary studios or present-day ideas?

(c) „Algorytmy Nowoczesności. Architektura jako narzędzie kształtowania polskiej tożsamości narodowej 1918-1939, Photo: Polski Instytut w Berlinie

The exhibition “Poland. Arquitectura” presented in Mexico City, Guadalajara and San Miguel de Allende shows the most important Polish projects from 2010 – 2016, such as the Copernicus Science Centre in Warsaw, the Philharmonic in Szczecin or the European Solidarity Centre in Gdańsk. The exhibition was prepared by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and promoted by the Polish Embassy in Mexico; it proved to be very successful and toured in 2018. The cultural attaché Zofia Ziółkowska stated that nearly 10,000 visitors have seen the exhibition at the Museum de Artes in Guadalajara. During the event, the Polish architect Anna Mieszek delivered lectures on Polish architecture at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM).

It is pertinent to note that the exhibitions presenting Polish projects are mainly the result of the work of Polish cultural institutions or Polish curators. Perhaps the hermetic character and unavailability of sources makes it difficult for foreign curators, critics and journalists to acquire information. The Adam Mickiewicz Institute responsible for promoting Polish culture does not even have an architectural division. It may be surprising, but, on the other hand, architecture and construction are a business, so studios should want to ensure good marketing and customers. Polish curators and architecture critics are basically absent from the global market. The situation is different in the field of art where Adam Szymczyk and Anda Rottenberg are certainly recognizable.

There was talk about the New Generations-Building The Atlas, a cyclical event organized by the Madrid Itinerant Office, which took place in Warsaw. 25 young studios participated in it, including BudCud, Atelier Starzak Strebicki, Paulina Grabowska and Centrala. It was the fifth edition of the festival, which was previously held in Milan and is run by Gianpiero Venturini from Itinerant Office. According to Domus, it is a meeting about emergent architects. BudCud and Centrala are not young offices anymore; they have clearly defined interests and program. Shouldn’t we look for new young “emerging” architects?

There were no Poles in the most important and / or the most popular events, such as: London Architecture Festival, Modesta Architecture Festival, World Architecture Festival and Design Indaba.

Implementations

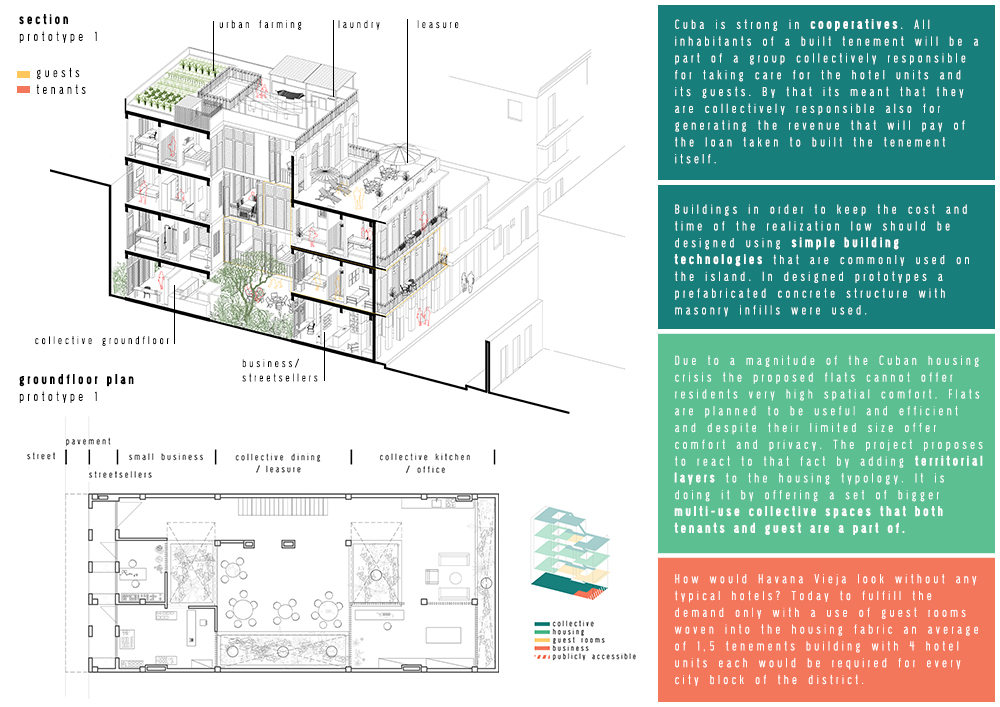

The architectural project (!) most frequently discussed in the global media was the NAVE (NAWA) by Oskar Zięta. Let me explain: NAWA is a large-scale sculpture, a spatial installation. It demonstrates how an innovative technology can work on the borderline of art and architectural design. In addition, there was a discussion of the building Bałtyk designed by MVRDV, the building of the Faculty of Radio and Television of the University of Silesia designed by the Spanish office BAAS Arquitectura. The Sprzeczna 4 project of the BBGK studio received recognition and publicity in the media. It is not surprising, as it is a return to the culture of prefabrication – very popular in the Polish People’s Republic and nowadays once more widely discussed. It is the second project designed by BBGK studio noticed in the European discourse, after the Katyn Museum.

(c) Nawa – Architectural Sculpture, Photos: Łukasz Gawroński

(c) Bałtyk, Photos: Ossip van Duivenbode

(c) Silesia University’s Radio and Television department, Photos: Adrian Goula

(c) Sprzeczna 4, Photos: Juliusz Sokołowski

Architectural competitions

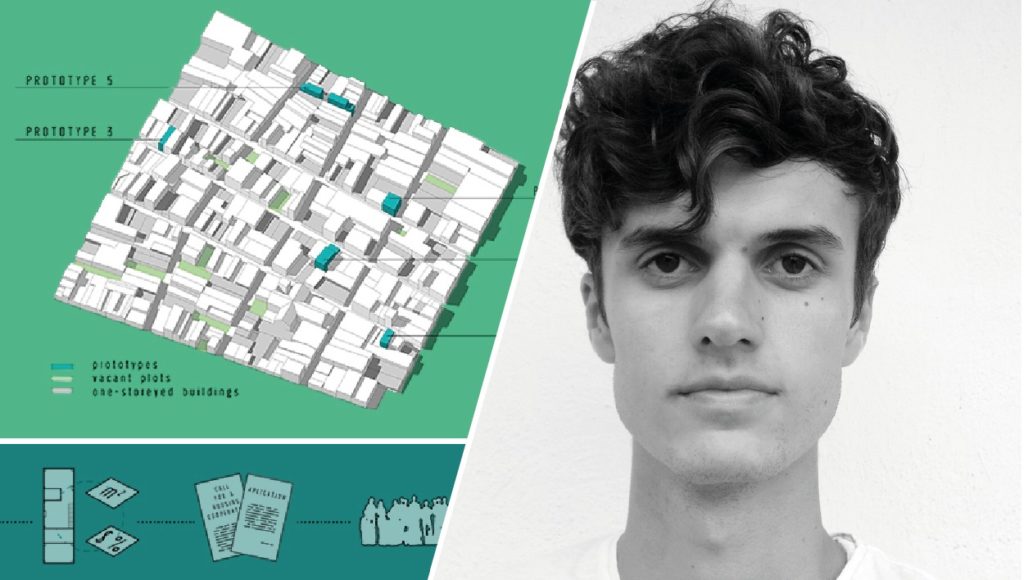

YTAA – Young Talent Architecture Award is a place for young designers to present their ideas. From hundreds of submitted projects, two Polish projects were selected. Tomasz Broma’s project regarding the self-organizing structures of housing units and the research by Iwo Borkowicz on the symbiosis between social housing and tourism in Havana. FAP opens the door to the most important institutions and architectural events in Europe, such as MAXXI in Rome, Strelka in Moscow or Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon.

(c) A symbiotic relation of cooperative social housing and dispersed tourism in Habana Vieja / Iwo Borkowicz, Faculty of Architecture, University of Leuven

(c) S’lowtecture. Housing structure in Wroclaw-Zerniki / Tomasz Broma, Faculty of Architecture, Wroclaw University of Technology

The Polish team of Damian Granosik, Jakub Kulisa and Piotr Pańczyk won the conceptual competition eVolvo 2018. Shelter Zip is a project of a high-rise building designed for post-disaster areas. eVolvo is a platform that has been for several years awarding the boldest conceptual project in an annual competition. After winning a prize in such a competition one can appear in the media and establish a studio to design bold projects.

(c) Skyshelter.zip: Foldable Skyscraper for Disaster Zones, Damian Granosik, Jakub Kulisa, Piotr Pańczyk

In year’s edition of the Mies van der Rohe Award, the Foundation has nominated 18 projects from Poland (there are 383 nominations in total). A nomination is the first stage in the competition rewarding the best projects. In the second stage, a shortlist of project is selected, then the finalists, and finally the winner.

Architectural research

It is worth taking a look at Łukasz Stanek, a researcher affiliated with the University of Manchester, who published two books in English (i.e. widely available and understandable) about Lefebvre and Team 10 East in 2014. Last year he gave lectures at conferences across the world (from Japan to United States) about Polish architecture in the socialist era, and Polish planners working, for example, in Lagos, Baghdad, Kuwait and Abu Dhabi. A book concerning the issue is to come out in English in 2019. Stanek’s work certainly contributes to the promotion of Polish architecture and thought. It is a pity, however that it also concerns merely the history of Polish architecture.

About architecture

The New York Times writes about Polish brutalism and modernist architecture. In his text on post-war Polish architecture Akash Kapur lists the most important examples, such as Spodek, Supersam, Bunkier Sztuki, Rotunda and discusses the turbulent history behind them. He talks about the blocks of flats in TriCity called falowce, the building at Smolna 8 in Warsaw and the Forum Hotel in Cracow. The interest in “badly born” [a term coined by Filip Springer and Marek Woźniczka to describe the architecture from the Polish People’s Republic] appears to be a continuation of the popularity, which begun with this year’s exhibition “Toward Concrete Utopia” about Yugoslavian architecture presented at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

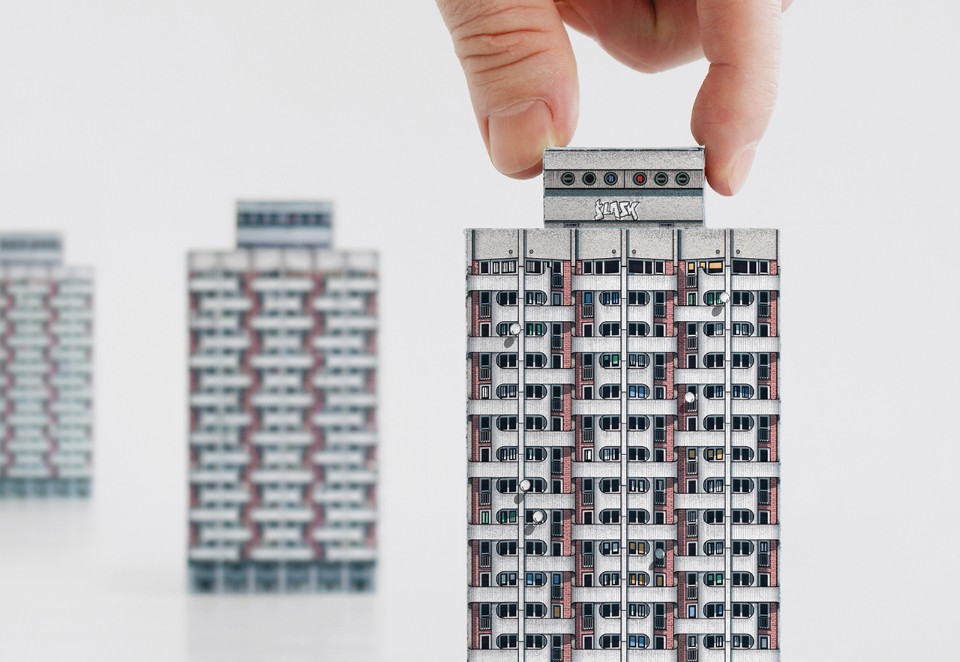

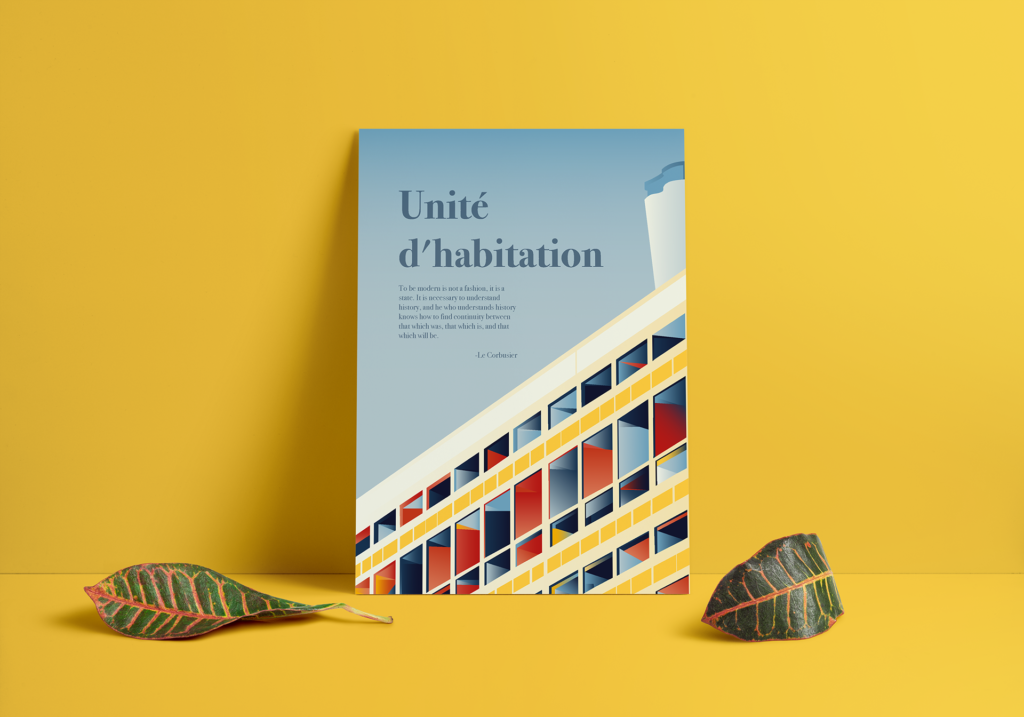

Domus discusses on its website the project “Eastern Block” by Zupagrafika – a collection of paper cut-out models of Eastern European icons of architecture of brutalism. The project of the Spanish-Polish design studio included, for example, the Wrocław Manhattan. Such “iconization” of architecture tends to lead to travels and learning about new places. It is pertinent to mention the work of Zuzanna Gadomska, who was invited by the Foundation Le Corbusier to prepare a series of architectural illustrations.

(c) Brutal East, Zupagrafika

(c) UNITE D’HABITATION illustration – Zuzanna Gadomska

The emigration continues

In 2018 Polish students and young architects continued to emigrate. The representatives of “Generation Z” are fluent in foreign languages, they have travelled a lot, and they have no complexes. They leave Poland in search for higher quality education. In comparison with the first years (2004-2008) when it meant a lot to leave the country, now it is easy to begin studies at the best European universities. Students choose master’s programs or workshops. An increasing number of young Polish architects study at the leading European universities: Accademia di Architettura di Mendrisio, ETH in Zürich, TU Delft, Politecnico di Milano, AA School of Architecture and The Bartlett in London, KADK in Copenhagen, and IAAC in Barcelona. It is only natural that the majority of Polish student begin apprenticeship or training there. Thus, my Linkedin is filled with wonderful information about internships in BIG, OMA, Herzog & Meuron, etc.

It would appear that Polish architectural universities don’t perceive this situation as problematic. Zuzanna Skalska, a trend analyst responsible for design, innovation and business, has repeatedly emphasized that these universities employ unqualified staff and that she wouldn’t advise anyone to study there. It is an obvious generalization, however, staff, learning conditions and curriculum require an urgent change. The idea of a new school of architecture created with the support of the School of Form in Poznań sounds very promising. Unfortunately, in hasn’t been launched in 2018.

Nihil Novil