Sprawl has come to Poland. That is what is evident from “Trouble in Paradise,” the display the curatorial team PROLOG mounted at the Venice Architecture Biennale this year. With a scenography that is so simple that it risks not giving the strangeness or scale of the issue its full due, the team both presents evidence of what is going on in the countryside of the fastest-growing country in the former East Europe, and offers some rather fanciful solutions as to how the situation could improve.

Aaron Betsky

The exhibition is timely. As an outsider, it is disappointing to see that some of the approaches the country previously seemed to be adopting from Northern Europe, namely the development of expansion areas on the urban fringe that were guided by the government at various levels and that sought to create more concentrated, shared housing forms grouped around both civic and educational facilities and public transit, have given way to the kind of laissez-faire accommodation to the development of single-family homes for those who can afford them, often on the site of small former farmsteads that are now useless because of the consolidation and industrialization of agriculture, that is common in the United States and many other countries.

The curators were careful to place the conditions in Poland in an international context, inviting critics (Platen Issaias and Hamed Khosravi, Pier Vittorio Aureli, Andrea Alberto Dutto, Katarzyna Kajdanek, Lukasz Moll, and Jacenty Dedek) to analyze the conditions of sprawl as they exist in many places. They did so with great clarity and verve. What is especially clear in PROLOG’s approach is the manner in which the curators and critics consistently zoom in, both in the texts and in the plans of existing landscapes and buildings, from the global to the local and particular. They note everywhere the breakdown of ordering systems that are recognizable. These include a geometry based on fields and pastures, as well as on a hierarchy of local, regional, and larger roads and the forms of buildings that developed over the centuries and even millennia based on their function as either storage or living structures. Instead, the hopscotch placement of structures across the landscape in such a way as to maximize property use, storage, or access, is now married with forms that appear almost automatically, and that denote little in terms of function or place.

Trouble in Paradise Photos. Jacopo Salvi

Trouble in Paradise Photos. Jacopo Salvi

The condition in Poland seems to be even more extreme than they are in some other areas of Europe for several reason. One is the speed with which the transformation of the economy is leading to these changes. This leaves little time for infrastructure, whether of a social and cultural nature, or of a transportation kind, to catch up. Nor can architects and designers develop responses to these new conditions with enough alacrity. In addition, the area where most of this sprawl is occurring is relatively flat and featureless (at least to an outside observer), giving few excuses for particularities or idiosyncrasies.

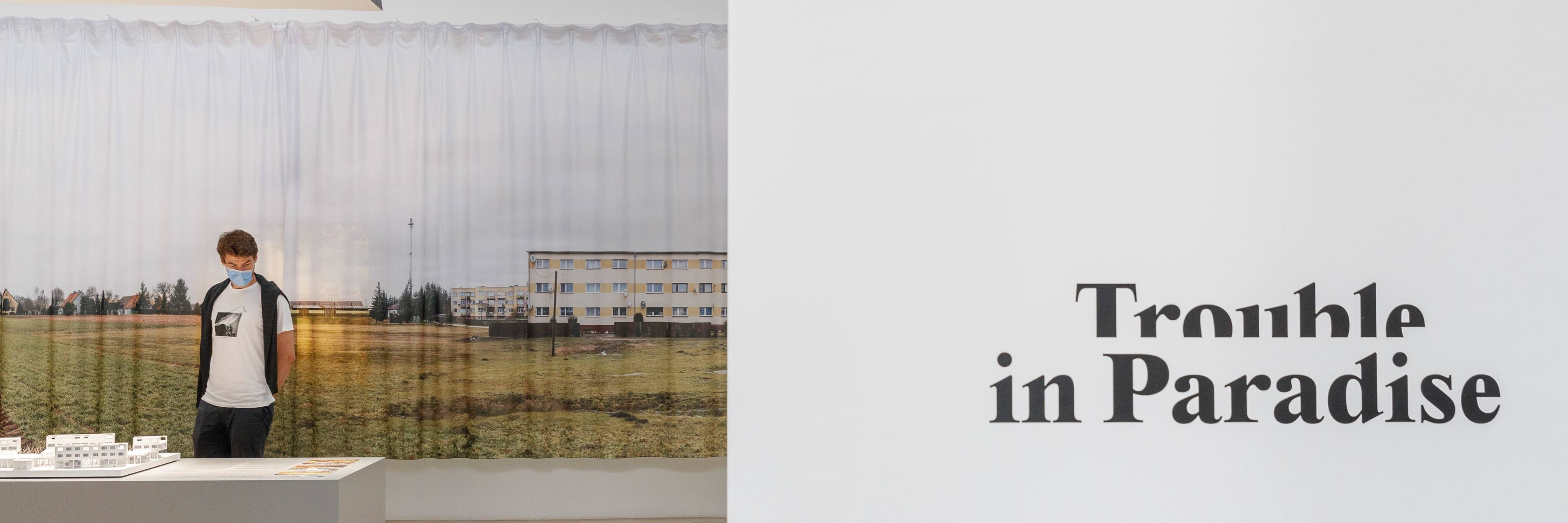

The exhibition –unlike the catalog—unfortunately shares some of the same problems of definition and differentiation. The curators have hung the walls of the space with curtains on which photographs of current conditions are printed. Though the photographs by Jan Domicz, Michel Sierakowksi, and Pawel Starzec, are beautiful and evocative, the display technique leaves the images unclear. This might be appropriate for the “terrain vague” that is the subject of this show, but it does not translate the data presented in the catalog into enough detail to allow us access to the current conditions in Poland in particular.

The solutions the curators commissioned from a select group of architects, and which they presented in computer-printed models and reproductions of drawings in the hall’s middle, also have a somewhat generic feel. Atelier Fanelsa, Gubahamori, KOSMOS, Rural Office for Architecture, RZUT, and Traumnovelle, who hail from various European countries, all offer version of social-democratic utopias of the 21st century variety, which is to say the kind of architecture that a good environmentalist would support. Most of them assume shared structures. Instead of the buildings now prevalent in the Polish landscape, which house families, goods, or farms, they propose creating lines of grids that will house everything from solar collectors and other forms of sustainable energy harvesting, to greenhouses, to collective housing.

The images that result are seductive. Rendered in soft hues and filled with happy families, they show a new kind of generic architecture, in which structure is an enabler whose neutrality ensures democratic access and the efficient use of resources. This is a world of communes or at least benevolent capitalism inhabited by a true middle class that has enough resources to live in this happy version of a new merger of agriculture, production, and suburban living.

I am afraid that I was indeed seduced, but not convinced. As I have often found in the attempts by architects to respond to sprawl, there is a disconnect between the analysis of what is going on now and the proposal for the future. Rather than recognizing that the desire for space, both within the house and around it, is strong enough that people are willing to sacrifice a great deal of time and money to achieve it, they propose that people will willingly live in an exiled version of an urban block. Rather than recognizing the injustice that is part and parcel of the capitalism that Poland under the current regime has embraced with such fervor means a differentiation in housing and usage types, they want to legislate equality through architecture. And, rather than recognizing the messy vitality and brutality of both agriculture and industry, even of the sustainable kind (have you ever opened your nose in an organic farm?), they present a fairy tale version of a new ecotopia.

This is, by the way, their aim. The curators say about their intention that the kind of exurban movement is being, and should be reversed:

The curators of the exhibition believe that the perception of the countryside through a lens of simplifications and stereotypes — treating it as a lost paradise, or a place where one can rest from the troubles of civilisation — is a significant problem. It turns out that the ideal of living near the city has a short shelf life. The pandemic, which led to a rise in migration to suburban areas around the world, has brought to light the daily struggles the Polish countryside has faced for years — including the lack of public transport, universal access to the internet or integration between the ‘newcomers’ and the local population.

‘The countryside is less and less often a promise of autonomy and escape from the city, and more and more often a storage space, a place for ring roads, production halls, farms, all the infrastructure without which life in large agglomerations would be impossible. This is primarily due to the convictions that the countryside is there to serve, acting as support facilities for the cities. We want to reverse this perspective, to stop thinking of the countryside from a “city dweller” point of view,’ says Robert Witczak of the PROLOG +1 curatorial team. ‘It’s important to us to show the countryside not as a closed, divided and privatised space,

Trouble in paradise Photo. Jacopo Salvi

Yet the pandemic is actually causing house prices in the countryside to go up, and cities to becoming more sprawling around the world. Moreover, the growth of warehouses and industrial structures does not preclude residential sprawl, but actually goes hand in hand with this kind of featureless construction. Sprawl is here to stay, in Poland and everywhere else.

Nonetheless, this exhibition has performed a great service. It has not only commissioned writing and analytic drawing of great clarity, precision, and perception, but has also given architects in Poland a chance to dream, and to provide counter-models. The point is not that these models should be implemented, but that they should provide a counterweight to the ugliness, environmental destruction, and social inequity that is currently being built into the landscape of Poland. I hope that a future regime can learn from the imagination and knowledge these architects have presented.

Aaron Betsky – one of the most prominent architecture critics in the world, curator, educator, lecturer, and writer of texts about architecture and design. He is the former director of the Cincinnati Art Museum and dean of the School of Architecture at Taliesin (formerly the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture).