The Power of Connections

In our daily routine, we sit at a clean desk in a beautiful interior and begin designing elements that are highly commercial. They further develop the world, also in the realm of consumption, as we create beautiful hotels, apartments, houses, and so on. I feel like finding time for charitable activities is a kind of solution to creating meaning – with the twin sisters, Magda Federowicz-Boule and Anna Federowicz, who run their studio along with Jarosław Gwoźdź, we talk about the beginnings of merging their design offices under the brand Tremend, and what Polish architecture can learn from abroad professionals.

Magda Federowicz-Boule i Anna Federowicz, photo. Bartek Barczyk

Marcin Szczelina: This issue of “Architecture Snob” is about mindfulness and care in architecture. What do these two concepts mean to you?

Magdalena Federowicz-Boule: I think we need to go back to the roots, to social and simple architecture. For me, it’s exemplified by what we did with Architects Without Borders, of which I am a co-founder. We created an ecological courtyard for the Dajemy Dzieciom Siłę foundation (We Give Children the Power) —a small space in Warsaw on Przybyszewskiego Street. We worked pro bono to help fellow human beings. That’s how I perceive architecture – as something from people for people. Additionally, thinking about modularity, simplicity, and multifunctionality is the future, applicable to both developing and developed countries.

Anna Federowicz: We are now starting to work on international projects. To win those, we need to be competitive in design, be curious, and pay attention to detail. Creativity is important to us—we’ve learned it and are trying to develop it within ourselves. Returning to the basics is also crucial—understanding for whom and why we create architecture. This is becoming increasingly important in the contemporary context. The world said, “never again wars,” but we already have at least two serious ones, and there are probably more playing out at the local level.

At Gaza, hundreds of people are dying every day, and there is an ongoing war on our eastern border as well. It is said that we need to completely change our habits—not only in ourselves but also in the way we create architecture. What is happening in the world prompts reflection on the meaningfulness of all actions taken.

MF-B: I recently attended an excellent geopolitical lecture in Cannes that addressed the wars you mentioned, and I can say that everything happening in the world is frightening. In the face of such phenomena, you really question why you do everything you’re currently doing. Nothing is straightforward or evident, as in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, for example. It’s challenging to find one’s place in all of this as a human and take a clear stance.

AF: Magda and I had the honor of traveling to Ukraine for two projects. Our physical presence wasn’t necessary there, but the mental support for people on the site was crucial. It showed that the world is still functioning, and we can count on each other.

And how does the Architects Without Borders initiative translate into real actions?

MF-B: The courtyard for the Dajemy Dzieciom Siłę foundation was a real action; the rest is quite theoretical. We are in contact with various universities and activists; there was recently a gathering in Copenhagen. When there were issues in Nepal related to an earthquake, we designed theoretical toilets as part of exercises, but some of them were actually implemented. These were places that also served as bathhouses for women, located near small gas stations and in large cities. In Uganda, we also worked on a theoretical project for a facility for the local community—a meeting place for fetching water. Architects reach out to us needing financial assistance, but that’s not our activity. Instead, we can support reconstruction initiatives.

AF: In our daily work, we sit at a clean desk in a beautiful interior and begin designing elements that are highly commercial. They further develop the world, also in the realm of consumption, as we create beautiful hotels, apartments, houses, and so on. I think finding time for charitable activities is a kind of solution to creating meaning. Helping my previous studio build a school in Haiti was a real action. A beautiful educational institution was created, but the whole process involved struggling with local authorities and the system.

We’re talking about making commercial interiors as sustainable as possible, which is a significant challenge in interior design because there are few certifications in this area. Do you try to focus on more eco-friendly solutions in your work? It can be difficult because they are more expensive, and investor’s Excel is inflexible.

MF-B: Intuition worked for us because we started with the renovation of old post-communist Orbis hotels, which we called “dungeons” because they were giant, unused spaces. Even then, we had the spirit of ecology, but we didn’t call it that because in a specific budget, we simply had to preserve a lot of materials and not throw everything away. Recycling and upcycling happened. We still stick to this intuitive ecology because it’s one of the pillars we set as a goal. First, we stop and revive what is possible, and only then do we think about new materials. And if they are new, they should be local to minimize transportation. The fact that eco-friendly materials are more expensive, in my opinion, doesn’t matter that much because we create objects that consume less energy and are quite costly themselves. In the long run, their profitability is much better.

AF: On the one hand, there is what we as architects can do. On the other hand, there are the companies we choose. We check whether they produce in an eco-friendly way and how they transport their products. We are also connected with the buildings we design on a mass scale. They have certificates and their appropriate hierarchies. We persuade investors to adopt such an approach. Currently, even residential buildings are starting to get certified. The selling price should also be dependent on how the object functions later and how much its operation costs, which is not a common approach even in products. Once, we produced household items that could survive in good condition for over 20 years, and today their life cycle is very short. The question is, where are we all heading.

I’d like to go back a bit to the beginning and ask when you two realized that you wanted to pursue design and architecture in general?

MF-B: There was never a specific moment. We come from a time when everything was very simple in life. We didn’t come from a very wealthy family, and to make ourselves a toy, we used to build ant houses with sticks. Back then, we didn’t know we would become architects. Choosing architecture in college, for me, was simply because I loved drawing, building, and creating.

AF: I would also emphasize creativity, which has been in us since a very young age. In addition to drawing, we were quite strong in mathematics, highlighting the engineering aspect. We went not only into interior architecture but also into creating and designing buildings because they are inseparable at the Warsaw University of Technology. We also had the opportunity to study in the USA as part of an exchange program—there was a similar approach there. Besides everything else, our early adulthood coincided with challenging times for Poland, so we were thinking about so-called ‘solid professions’, which being an architect falls under.

I know that initially, you both ran your own studios separately. When was the moment when you decided it was time to join forces?

MF-B: We ran them separately because in the life of twins, each one seeks her own identity.

AF: It started with living in communism, where clothes were rationed. Whenever Dad bought us shoes, they looked exactly the same.

MF-B: Seeking that mentioned identity also involved separating from each other for a longer time so that each could find herself and discover what she wanted to do. Ultimately, we collided at a similar point because we both created volumetric architecture and larger interior projects.

AF: We also belong to those sisters for whom each apple must be divided perfectly evenly in half, down to the millimeter. It has its advantages, of course, as no one is ever disadvantaged, but it also arouses competition. Initially, this led us to conclude that we couldn’t work together. We were too close as friends and loved each other. We knew that before the merger could happen, each of us had to achieve something uniquely of her own.

MF-B: It’s a process of maturing. It’s an absolute process for every twin that they have to find themselves to then do interesting things in a group, especially with their biological other half.

AF: We started by collaborating on significant projects, such as Łódź Fabryczna. We realized that it’s easier to tackle such a big topic with two studios.

MF-B: Each of us also has different experiences. I lived and worked in France for a while.

AF: In turn, I worked in Luxembourg and Belgium. These are all Francophone elements, but each of us initially chose her own solid and interesting path.

What was the most significant joint project that showcased your strength, was it the mentioned Łódź Fabryczna?

MF–B: Yes, it was a project where we learned a lot together—collaboration, managing people, industries, and details. It was simultaneously challenging because it was enormous, oversized, and from the beginning had unrealistic Franco-Dutch assumptions. It was meant to be a station like in Rotterdam or Lyon, driving the city’s development, a kind of revitalization of the space.

AF: I would look at it more broadly because we remember times when there were no roads in Poland at all, and now we have a good network of highways. Once, we could dream of getting on a train in Warsaw and getting off in Paris in a few hours. Maybe we can also make it so that we will be part of the European high-speed railways. The Łódź Fabryczna project revitalized a city that was depopulating due to its proximity to the capital. Offices and hotels appeared around the station, and if we connect it with the railway, there will be even more revitalization. Especially since Poznań is also on the route, which was once said to be depopulating. A large station is a very interesting challenge because we learn everything, we have consultants.

MF-B: From that, a smaller project in Lublin emerged, which we thought through from start to finish. The city’s programmatic assumptions were that long-distance and city buses should be practically in the center. On the one hand, this raised our controversies, but on the other, it sparked a long debate on the subject. It turned out that this sort of transportation hub eliminated, for example, the need to use taxis, which is eco-friendly outcome in itself. Other solutions were added, such as heat pumps, concrete accumulating and releasing energy, or natural ventilation.

AF: A simple shelter could have come out of a public tender, but it ended up being practically a competition-winning project.

We talk a lot about the success of architects outside of Poland. However, often when visiting the websites of the most famous architecture firms globally, it’s challenging to distinguish between visualizations and realizations. Unfortunately, I don’t see you in these rankings, although I know that you extend well beyond the Polish context and have had many successes in this area.

MF-B: Traveling abroad is the result of hard work; unfortunately, you don’t find projects on the street. Initially, we were strongly connected to shopping malls. We had many investors from France or South Africa, but they were investing in Poland. Shopping malls eventually became less appreciated, so our foreign partners started expanding into the hotel industry. They took us along with them. We traveled to France, and they trained us on how they create their brands – Novotel, Mercure, MGallery, Pullman, or Accor. With the Accor hotel chain, we won two international competitions in Budapest. That was the first time we competed with the English and French firms in a closed competition and won. We also began to work with other brands – Marriott, Hilton, Vienna House, IHG, MENNINGER.

AF: It’s worth adding that in international competitions, you the lowest price is not the winning criteria but design.

MF-B: Also, the story we create around the project makes the difference when it comes to winning.

AF: In addition, we have keys to several properties, which is a proof that we don’t only operate with visualizations. It opens doors.

MF-B: Earlier, we Polish-ized French projects; now, as Poles, we are equal participants in international competitions. Reliability has never been lacking in our nation, but we learned about design by visiting hotels that our foreign partners considered particularly noteworthy.

How does it feel like when you go abroad and see your buildings in well-known European cities?

MF-B: We are pleased with ourselves, especially because we learned from professionals abroad, and suddenly we competed with them. Moreover, these are objects that our investors consider successful. I am a somewhat critical person, and when I enter a finished building, I feel like something could always have been done better.

AF: These are reflections from which lessons are drawn for the future, to design even better, more functionally, and with more design. One thing is constant – we always try to make our buildings timeless – without loud colors and materials.

Your studio is quite large; do you find space for creative activities within managing it?

MF-B: We employ around 100 people, including 9 in the sanitary department. One of our partners is an engineer, and we also have a few project managers. There are almost 80 architects.

AF: Our strength might be that when we joined forces, our partner Jarek, who is responsible for the technical sphere, gave us space for creativity. We participate in discussions with investors about the concept and development of the project. I am at least every 3 weeks on the construction site, and there are projects which I visit weekly. Magda does the same. We can afford it because we have significant technical support.

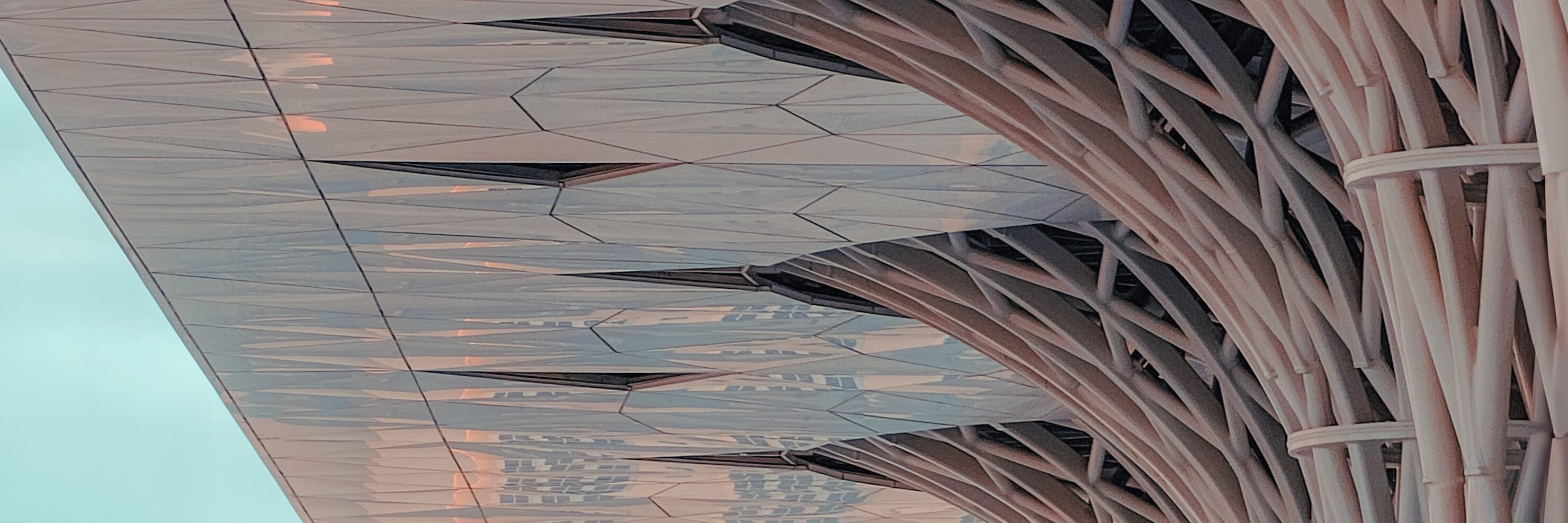

Project Metropolitan Railway Station in Lublin, photo by Rafał Chojnacki

While working together, there are probably moments of disagreements, which is natural in the design process. How do you manage to combine working together with sisterhood?

MF-B: We have always been an Italian family when it comes to expression. We really like spending time together, not only at work but also on vacation. We have similar energy and interests. When we go to the mountains, we like to tire ourselves out so much that we have no strength for anything else. Of course, tensions also happen due to the amount of time spent together.

AF: That’s why we have our own families and many friends, to balance and find refuge among them.

What should I wish you for the future?

MF-B: An optimal amount of working time.

AF: We have a lot of energy, but on the other hand, we need calm.

MF-B: Also, we would love to have more international projects because they are a great cultural adventure. We have always loved traveling – it’s our second leg not related to business. If you can incorporate it into the company, it’s a reason to love your job. Of course, it can be tiring, but staying only in Poland would be limiting.

MF-B: Sometimes I can go to my home in France for 4 days just to unwind, but I work there just the same.

AF: These trips are not only relaxation but also a change of environment. It’s as important as meeting and recharging with other people.